Your weekly guide to Sustainable Investment

TBLI Capital Connect

Your Gateway to Mission-Aligned Investors – Apply Now to Raise Capital for Impact

Why TBLI Capital Connect?

✅ Access to a curated network of high-net-worth investors and venture capitalists

✅ Tailored matchmaking to align you with the right funding partners

✅ Streamlined process to fast-track your fundraising goals

✅ Different tiers of service, offering you the most suitable service according to your budget.

More details here

Would you like to book a call to discuss in detail? click here

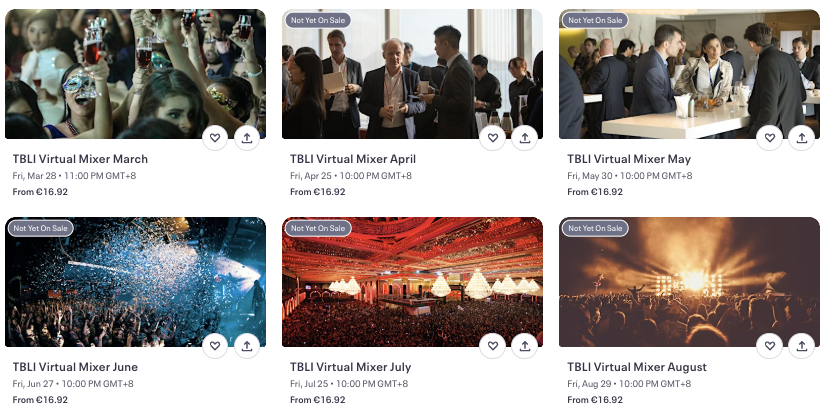

Upcoming TBLI Virtual Mixers

TBLI Radical Truth Podcast

More than Carbon or bips. How AI is increasing ESG Impact Investing 10-fold

Three things that people will learn from this podcast:

- Expanding ESG Impact Investing Beyond Carbon Footprint

- The Role of AI in Identifying Impact Opportunities

- Quantifying the Impact of ESG Investing with AI

Olinga Taeed is Director of the Centre for Citizenship, Enterprise and Governance, the world’s leading not-for-profit think tank on the Movement of Value with over 220,000 members, and is Expert Advisor and Council Member of the Chinese Ministry of Commerce’s ‘Blockchain E-Commerce Committee’.

He was the world’s first blockchain professor at Birmingham City University, and is Chief Editor of Frontiers in Blockchains (Switzerland), a peer review academic journal with 400+ editors. He is Chair of Arbor Verification Tech (ESG – Ho Chi Minh), MiMeta.Life (Metaverse), Bureau of Media Data and Ideology (Media – New York), and AizaWorld (Gaming – Hanoi); most recently he was appointed Chair of AITEA (AI - Beijing) populated by staff from tech giants Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent.

He has spoken at The Vatican which attributed him with the “God Metric – the fastest adopted social impact metric in the world”, and is Advisor to Wildcat Petroleum Plc, a London Stock Market listed company.What will you learn:

Join TBLI Circle and expand your Impact network

Step into a community of purpose-driven professionals transforming finance for a sustainable future. At TBLI Circle, you’ll connect with authentic leaders, discover breakthrough opportunities, and gain insights that drive real impact. Expand your network, elevate your influence, and accelerate your journey in ESG and impact investing. Don’t just talk about change—be the change.

Expand your network, elevate your influence, and accelerate your journey in ESG and impact investing. Don’t just talk about change—be the change.

ClimateForce impact report 2019-2025

''The Daintree, like many tropical regions, has seen significant land-use change over the decades. Agricultural expansion has shaped the landscape, creating both challenges and opportunities for diversification. ClimateForce is working not just to restore the rainforest, but to enhance its resilience, ensuring that biodiversity thrives while supporting a balanced approach to land management.

This is about more than tree planting; it’s a model for nature-based solutions at scale. Through strategic reforestation, ecosystem regeneration, and sustainable land practices, we are demonstrating how conservation and economic stability can go hand in hand.

Please do consider spending a few minutes to read our report and in doing so, please also consider whether you and your organisation can help us through supporting their R&D and the investments to follow, as we redouble our efforts and prove to the world we have a model here that can benefit many rural communities globally.

Finally, and of huge importance, a heart felt thank you on behalf of Barney and his team to those that have supported the journey so far. Without you, none of this would be possible.

Please do consider reposting and sharing this update. Doing so will be highly appreciated.'' - Kevin McCollough - ClimateForce, Chair.

Read the full report

Microplastics hinder plant photosynthesis, study finds, threatening millions with starvation

Researchers say problem could increase number of people at risk of starvation by 400m in next two decades

The pollution of the planet by microplastics is significantly cutting food supplies by damaging the ability of plants to photosynthesise, according to a new assessment.

The analysis estimates that between 4% and 14% of the world’s staple crops of wheat, rice and maize is being lost due to the pervasive particles. It could get even worse, the scientists said, as more microplastics pour into the environment.

About 700 million people were affected by hunger in 2022. The researchers estimated that microplastic pollution could increase the number at risk of starvation by another 400 million in the next two decades, calling that an “alarming scenario” for global food security.

Other scientists called the research useful and timely but cautioned that this first attempt to quantify the impact of microplastics on food production would need to be confirmed and refined by further data-gathering and research.

The annual crop losses caused by microplastics could be of a similar scale to those caused by the climate crisis in recent decades, the researchers behind the new research said. The world is already facing a challenge to produce sufficient food sustainably, with the global population expected to rise to 10 billion by around 2058.

Microplastics are broken down from the vast quantities of waste dumped into the environment. They hinder plants from harnessing sunlight to grow in multiple ways, from damaging soils to carrying toxic chemicals. The particles have infiltrated the entire planet, from the summit of Mount Everest to the deepest oceans.

“Humanity has been striving to increase food production to feed an ever-growing population [but] these ongoing efforts are now being jeopardised by plastic pollution,” said the researchers, led by Prof Huan Zhong, at Nanjing University in China. “The findings underscore the urgency [of cutting pollution] to safeguard global food supplies in the face of the growing plastic crisis.”

People’s bodies are already widely contaminated by microplastics, consumed through food and water. They have been found in blood, brains, breast milk, placentas and bone marrow. The impact on human health is largely unknown, but they have been linked to strokes and heart attacks.

Prof Denis Murphy, at the University of South Wales, said: “This analysis is valuable and timely in reminding us of the potential dangers of microplastic pollution and the urgency of addressing the issue, [but] some of the major headline figures require more research before they can be accepted as robust predictions.”

The new study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, combined more than 3,000 observations of the impact of microplastics on plants, taken from 157 studies.

Previous research has indicated that microplastics can damage plants in multiple ways. The polluting particles can block sunlight reaching leaves and damage the soils on which the plants depend. When taken up by plants, microplastics can block nutrient and water channels, induce unstable molecules that harm cells and release toxic chemicals, which can reduce the level of the photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll.

The researchers estimated that microplastics reduced the photosynthesis of terrestrial plants by about 12% and by about 7% in marine algae, which are at the base of the ocean food web. They then extrapolated this data to calculate the reduction in the growth of wheat, rice and maize and in the production of fish and seafood.

Asia was hardest hit by estimated crop losses, with reductions in all three of between 54m and 177m tonnes a year, about half the global losses. Wheat in Europe was also hit hard as was maize in the United States. Other regions, such as South America and Africa, grow less of these crops but have much less data on microplastic contamination.

In the oceans, where microplastics can coat algae, the loss of fish and seafood was estimated at between 1m and 24m tonnes a year, about 7% of the total and enough protein to feed tens of millions of people.

The scientists also used a second method to assess the impact of microplastics on food production, a machine-learning model based on current data on microplastic pollution levels. It produced similar results, they said.

Read full article

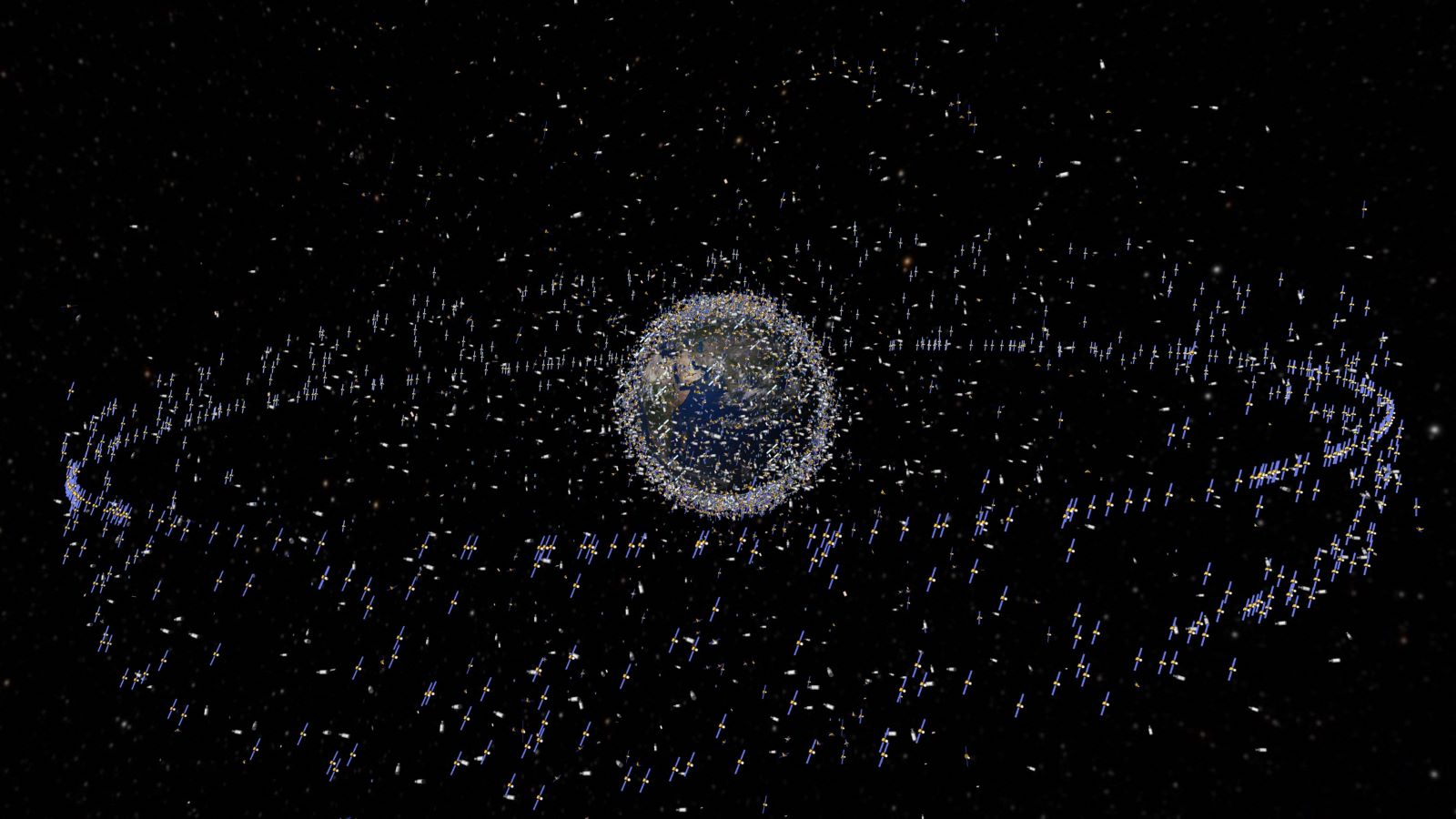

Earth orbit is filling up with junk. Greenhouse gases are making the problem worse.

By the end of the century, a shrinking atmosphere could create a minefield for satellites.

At any given moment, more than 10,000 satellites are whizzing around the planet at roughly 17,000 miles per hour. This constellation of machinery is the technological backbone of modern life, making GPS, weather forecasts, and live television broadcasts possible.

But space is getting crowded. Ever since the Space Age dawned in the late 1950s, humans have been filling the skies with trash. The accumulation of dead satellites, chunks of old rockets, and other litter numbers in the tens of millions and hurdles along at speeds so fast that even tiny bits can deliver lethal damage to a spacecraft. Dodging this minefield is already a headache for satellite operators, and it’s poised to get a lot worse — and not just because humans are now launching thousands of new crafts each year.

All the excess carbon dioxide generated by people burning fossil fuels is shrinking the upper atmosphere, exacerbating the problem with space junk. New research, published in Nature Sustainability on Monday, found that if emissions don’t fall, as few as 25 million satellites — about half of the current capacity — would be able to safely operate in orbit by the end of the century. That leaves room for just 148,000 in the orbital range that most satellites use, which isn’t as plentiful as it sounds: A report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 2022 estimated that as many as 60,000 new satellites will crowd our skies by 2030. According to reports, Elon Musk’s SpaceX alone wants to deploy 42,000 of its Starlink satellites.

“The environment is very cluttered already. Satellites are constantly dodging right and left,” said William Parker, a Ph.D. researcher in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the lead author of the study. In a recent six-month period, SpaceX’s Starlink satellites had to steer around obstacles 50,000 times. “As long as we are emitting greenhouse gases, we are increasing the probability that we see more collision events between objects in space,” Parker said.

Until recently, the effects of greenhouse gas emissions on the upper atmosphere was so understudied that scientists dubbed it the “ignorosphere.” But research using modern satellite data has revealed that, paradoxically, the carbon dioxide that warms the lower atmosphere is dramatically cooling the upper atmosphere, causing it to shrink like a balloon that’s been left in the cold. That leaves thinner air at the edge of space.

The problem is that atmospheric density is the only thing that naturally pulls space junk out of orbit. Earth’s atmosphere doesn’t suddenly give way to the vacuum of space, but gets dramatically thinner at a point known as the Kármán line, roughly 100 kilometers up. Objects that orbit the planet are dragged down by the lingering air density, spiraling closer to the planet until eventually reentering the atmosphere, often burning up as they do.

According to the nonprofit Aerospace Corporation, the lowest orbiting debris takes only a few months to get dragged down. But most satellites operate in a zone called “low Earth orbit,” between 200 and 2,000 kilometers up, and can take hundreds to thousands of years to fall. The higher, outermost reaches of Earth’s influence are referred to as a “graveyard” orbit that can hold objects for millions of years.

“We rely on the atmosphere to clean out everything that we have in space, and it does a worse job at that as it contracts and cools,” Parker said. “There’s no other way for it to come down. If there were no atmosphere, it would stay up there indefinitely.”

Parker’s study found that in a future where emissions remain high, the atmosphere would lose so much density that half as many satellites could feasibly fit around all the debris stuck in space. Nearly all of them would need to squeeze into the bottom of low Earth orbit, where they would regularly need to use their thrusters to avoid getting dragged down. Between 400 and 1,000 kilometers, where the majority of satellites operate, as few as 148,000 would be safe. More than that, and the risk of satellites crashing into debris or each other poses a threat to the space industry.

“The debris from any collision could go on to destroy more satellites,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts who was not involved with the Nature study. “And so you can get a chain reaction where all the satellites are hitting each other, breaking up, and creating more and more debris.”

This domino effect, commonly known as Kessler syndrome, could fill the orbit around Earth with so much destructive clutter that launching or operating satellites becomes impossible. It’s the runaway scenario that the paper cautions greenhouse gas emissions will make more likely. “But the chain reaction doesn’t happen overnight,” McDowell said. “You just slowly choke more and more on your own filth.”

Read full article

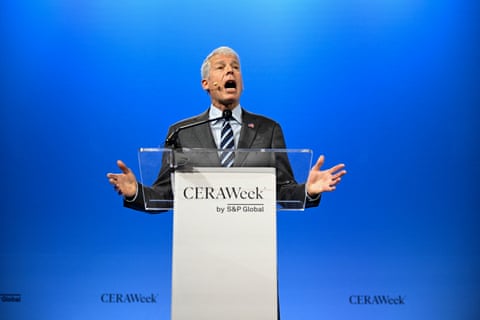

What the world needs now is more fossil fuels, says Trump’s energy secretary

Chris Wright signals abandonment of Biden’s ‘irrational, quasi-religious’ climate policies at industry conference

The world needs more planet-heating fossil fuel, not less, Donald Trump’s newly appointed energy secretary, Chris Wright, told oil and gas bigwigs on Monday.

“We are unabashedly pursuing a policy of more American energy production and infrastructure, not less,” he said in the opening plenary talk of CERAWeek, a swanky annual conference in Houston, Texas, led by the financial firm S&P Global.

Wright, a former fracking executive who was picked by Trump to the crucial cabinet position, also attacked the Joe Biden administration for focusing “myopically on climate change”.

“The Trump administration will end the Biden administration’s irrational, quasi-religious policies on climate change that imposed endless sacrifices on our citizens,” he said at the conference, for which tickets cost upward of $10,000. “The cure was far more destructive than the disease.”

Wright has been called a climate skeptic, for instance for repeatedly denying that global heating is a crisis.

“This is simply wrong: I am a climate realist,” he said.

“The Trump administration will treat climate change for what it is, a global physical phenomenon that is a side-effect of building the modern world,” he added. “Everything in life involves trade-off.”

Though he admitted fossil fuels’ greenhouse gas emissions were warming the planet, he said “there is no physical way” solar, wind and batteries could replace the “myriad” uses of gas – something top experts dispute. Further, a bigger and more immediate problem was energy poverty, Wright said.

“Where is the Cop conference for this far more urgent global challenge,” he said, referring to the annual United Nations climate talks, known as the Conference of the Parties (Cop). “I look forward to working with all of you to better energize the world and fully unleash human potential.”

The night before his CERAWeek plenary session, Wright had a meeting with top executives of fossil fuel firms including TotalEnergies, Freeport-McMoRan, Occidental Petroleum, and EQT, Axios and Reuters reported. Trump’s interior secretary, Doug Burgum, who will address CERAWeek attenders on Wednesday, also attended the dinner meeting.

Trump obtained record donations from the fossil fuel industry in his 2024 campaign. In April, he came under fire for a meeting at his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida, at which he reportedly asked more than 20 executives, from companies including Chevron, Exxon and Occidental, for $1bn and promised, if elected, to slash climate policies.

Under Biden, Wright said, ordinary Americans suffered. “The expensive energy or climate policies that have been in vogue among the left in wealthy western nations have taken a heavy toll on their citizens,” he said, putting the word “climate” in scare quotes.

US citizens “heat our homes in winter, cool them in summer, store period foods in our freezers and refrigerators and have light, communications and entertainment at the flip of a switch,” he said – a lifestyle that “requires an average of 13 barrels of oil per person per year”.

Meanwhile poorer countries lack energy, he said, meaning they need more fossil fuels.

“The other 7 billion people on average, consume only three barrels of oil per person per year,” he said. “Africans average less than one barrel.”

The comments came after Wright addressed the Powering Africa Summit in Washington DC on Friday, saying that it would be “paternalistic” and “100% nonsense” to encourage Africa to halt coal development because of climate concerns.

Read full article

America's Butterflies Are Disappearing At 'Catastrophic' Rate, Study Says

The number of the winged beauties down 22% since 2000, according to new research.

WASHINGTON (AP) — America’s butterflies are disappearing because of insecticides, climate change and habitat loss, with the number of the winged beauties down 22% since 2000, a new study finds.

The first countrywide systematic analysis of butterfly abundance found that the number of butterflies in the Lower 48 states has been falling on average 1.3% a year since the turn of the century, with 114 species showing significant declines and only nine increasing, according to a study in Thursday’s journal Science.

“Butterflies have been declining the last 20 years,” said study co-author Nick Haddad, an entomologist at Michigan State University. “And we don’t see any sign that that’s going to end.”

A team of scientists combined 76,957 surveys from 35 monitoring programs and blended them for an apples-to-apples comparison and ended up counting 12.6 million butterflies over the decades. Last month an annual survey that looked just at monarch butterflies, which federal officials plan to put on the threatened species list, counted a nearly all-time low of fewer than 10,000, down from 1.2 million in 1997.

Many of the species in decline fell by 40% or more.

David Wagner, a University of Connecticut entomologist who wasn’t part of the study, praised its scope. And he said while the annual rate of decline may not sound significant, it is “catastrophic and saddening” when compounded over time.

“In just 30 or 40 years we are talking about losing half the butterflies (and other insect life) over a continent!” Wagner said in an email. “The tree of life is being denuded at unprecedented rates.”

The United States has 650 butterfly species, but 96 species were so sparse they didn’t show up in the data and another 212 species weren’t found in sufficient number to calculate trends, said study lead author Collin Edwards, an ecologist and data scientist at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“I’m probably most worried about the species that couldn’t even be included in the analyses” because they were so rare, said University of Wisconsin-Madison entomologist Karen Oberhauser, who wasn’t part of the research.

Haddad, who specializes in rare butterflies, said in recent years he has seen just two endangered St. Francis Satyr butterflies — which only live on a bomb range at Fort Bragg in North Carolina — “so it could be extinct.”

Some well-known species had large drops. The red admiral, which is so calm it lands on people, is down 44% and the American lady butterfly, with two large eyespots on its back wings, decreased by 58%, Edwards said.

Even the invasive white cabbage butterfly, “a species that is well adapted to invade the world,” according to Haddad, fell by 50%.

“How can that be?” Haddad wondered.

Cornell University butterfly expert Anurag Agrawal said he worries most about the future of a different species: Humans.

Read full article

https://mail.tbligroup.com/emailapp/index.php/lists/cm138dw4qa9f1/unsubscribe