Your weekly guide to Sustainable Investment

TBLI Capital Connect Client Highlight:

Épopée Gestion

From smart EV charging and low-carbon data centres to the maritime sector, including hybrid wind-assisted container ships, Épopée is building the foundations of a net-zero future, one project at a time. An Article 9 SFDR fund with strong local roots and a mission-driven approach, Épopée Infra Climat I shows how climate impact and financial returns can be achieved outside the usual corridors of power.

Are you interested in engaging TBLI for our Capital Connect services? Book a call here

TBLI Radical Truth Podcast

How to create Impact in unstable frontier markets /w Michael Madden

Michael Madden has over 30 years of experience in Financial Services. His success has been built on inventive business intelligence, the ability to engage with international partners, and most importantly, as a leader and consensus builder. Michael has significant knowledge of the payments industry, both cards and digital, the retail banking sector, and as a business leader and entrepreneur in emerging markets.

Michael is the Managing Partner of Ronoc, an investment business he founded in 2008, which invests in financial services businesses with a focus on Central and Southeast Asia. He is the longest-serving board director of XacBank where his company Ronoc is a significant shareholder. In Myanmar, he is the founder and Chairman of OnGo, a market-leading digital payments business, that he launched in 2016.

What will you learn:

-How do you launch a fintech company in a country that lacks everything?

- How do you keep your staff safe during a coup?

-What are the greatest challenges in frontier markets?

Join TBLI Circle and expand your Impact network

Step into a community of purpose-driven professionals transforming finance for a sustainable future. At TBLI Circle, you’ll connect with authentic leaders, discover breakthrough opportunities, and gain insights that drive real impact. Expand your network, elevate your influence, and accelerate your journey in ESG and impact investing. Don’t just talk about change—be the change.

Expand your network, elevate your influence, and accelerate your journey in ESG and impact investing. Don’t just talk about change—be the change.

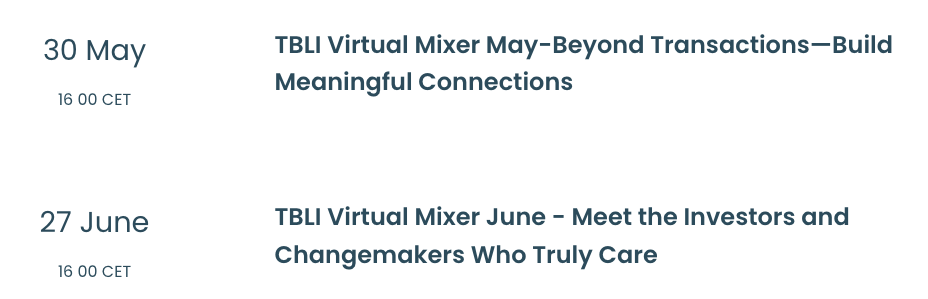

Upcoming TBLI Virtual mixers

Finance isn’t broken—it’s just misaligned. Realign it with us.

Support TBLI→ tbli.org

Spotlight Interview /w Sporadicate founder Gavin Pechey

Revolutionizing Remediation with Mycelium

In this spotlight interview, Sporadicate's founder Gavin Pechey shares his journey and insights into sustainable innovation. He discusses the challenges and opportunities in creating impactful solutions for a cleaner future, emphasizing the importance of values-based investing and community engagement.

Gavin's passion for environmental change and his commitment to practical action make this conversation a must-watch for those interested in sustainable development and impact investing

Why Trump can’t stop states from fighting climate change

Climate progress is still happening. You just need to know where to look.

The United States has never really cared much about tackling climate change, at least at the federal level. Up until the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA — which handed out billions of dollars for people to electrify their homes and pumped billions more into the clean energy economy — neither Congress nor the executive branch advanced truly meaningful climate policy, given the scale of the crisis.

Yet carbon dioxide emissions in the U.S. have fallen from 6 billion annually in 2000 to less than 5 billion today. For that, the country can largely thank its states and cities, which have embarked on ambitious campaigns to, among other things, electrify transportation, set automobile pollution standards, and incentivize the deployment of renewable energy. At the same time, wind and solar are now cheaper to build than new fossil fuel infrastructure, and there’s little Trump can do to stop those market forces from driving down emissions further.

Accordingly, Trump has set his sights on states during the first 100 days of his administration. He has tried to kill New York City’s congestion pricing, though last week the Department of Justice accidentally filed a document outlining the legal flaws with the administration’s plan. On April 8, he signed an executive order directing Attorney General Pam Bondi to identify and halt any state climate laws that she deems illegal, including California’s pioneering cap-and-trade program. That directive, though, is probably illegal because the Constitution guarantees states broad authority to enact their own laws, legal experts told Grist. “This is the world the Trump administration wants your kids to live in,” California Governor Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “California’s efforts to cut harmful pollution won’t be derailed by a glorified press release masquerading as an executive order.”

In a counterintuitive way, the lack of federal climate ambition has made what action has occurred more resilient because states are doing their own things and collaborating with each other. If the country had established a grand governing body years ago — something like an Environmental Protection Agency but focused exclusively on climate change — the Trump administration could easily dismantle it.

“States have been saying since the election that they retain the authority and the ability and the ambition to drive down pollution and keep America on track to meet its goals,” said Casey Katims, executive director of the U.S. Climate Alliance, a coalition of 24 governors (just one of them a Republican) focused on climate action. “This order is an indication that the president and this administration know that all of that is true.”

This is not the climate movement’s first tussle with an administration hostile to action. The U.S. Climate Alliance and America Is All In — a coalition of thousands of political, cultural, and business leaders — both formed after Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2017. States also now regularly share information with each other, like the best ways to encourage the construction of energy-efficient buildings and to replace gas furnaces with electric heat pumps. They’re also collaborating to modernize their grids to meet the extra demand that comes with widespread electrification.

“That relationship building and trust has not only allowed us to be truly a coalition, but it’s allowed us to move faster together on our climate action,” said Amanda Hansen, deputy secretary for climate change at California’s Natural Resources Agency. “The coalitions that came together very quickly in response to the first Trump administration are now significantly larger, more capable, and have really solid foundations for true collaboration.”

While California and other states will have to wait and see which climate policies Bondi deems illegal, they’re already fighting on other fronts in court. When the Trump administration froze nearly $3 trillion in federal assistance funds in January, including those provided by the IRA and the bipartisan infrastructure law, 23 attorneys general (including those in Republican-led Vermont and Nevada) sued, and a judge ordered the money released.

Disbursing these sorts of funds isn’t optional — it is required, because Congress passed legislation allocating them. To stop the flow of money, Congress would have to change the laws. “It’s just costing the taxpayers millions of dollars to address these lawsuits for congressionally authorized funds that were critical to addressing the climate crisis,” said Jillian Blanchard, vice president of climate change and environmental justice at Lawyers for Good Government, a coalition of 125,000 attorneys, students, and activists.

Read full article

Tensions over Kashmir and a warming planet have placed the Indus Waters Treaty on life support

By Fazlul Haq, The Ohio State University

In 1995, World Bank Vice President Ismail Serageldin warned that whereas the conflicts of the previous 100 years had been over oil, “the wars of the next century will be fought over water.”

Thirty years on, that prediction is being tested in one of the world’s most volatile regions: Kashmir.

On April 24, 2025, the government of India announced that it would downgrade diplomatic ties with its neighbor Pakistan over an attack by militants in Kashmir that killed 26 tourists. As part of that cooling of relations, India said it would immediately suspend the Indus Waters Treaty – a decades-old agreement that allowed both countries to share water use from the rivers that flow from India into Pakistan. Pakistan has promised reciprocal moves and warned that any disruption to its water supply would be considered “an act of war.”

The current flareup escalated quickly, but has a long history. At the Indus Basin Water Project at the Ohio State University, we are engaged in a multiyear project investigating the transboundary water dispute between Pakistan and India.

I am currently in Pakistan conducting fieldwork in Kashmir and across the Indus Basin. Geopolitical tensions in the region, which have been worsened by the recent attack in Pahalgam, Indian-administered Kashmir, do pose a major threat to the water treaty. So too does another factor that is helping escalate the tensions: climate change

A fair solution to water disputes

The Indus River has supported life for thousands of years since the Harappan civilization, which flourished around 2600 to 1900 B.C.E. in what is now Pakistan and northwest India.

After the partition of India in 1947, control of the Indus River system became a major source of tension between the two nations that emerged from partition: India and Pakistan. Disputes arose almost immediately, particularly when India temporarily halted water flow to Pakistan in 1948, prompting fears over agricultural collapse. These early confrontations led to years of negotiations, culminating in the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960.

Brokered by the World Bank, the Indus Waters Treaty has long been hailed as one of the most successful transboundary water agreements.

It divided the Indus Basin between the two countries, giving India control over the eastern rivers – Ravi, Beas and Sutlej – and Pakistan control over the western rivers: Indus, Jhelum and Chenab.

At the time, this was seen as a fair solution. But the treaty was designed for a very different world. Back then, India and Pakistan were newly independent countries working to establish themselves amid a world divided by the Cold War.

When it was signed, Pakistan’s population was 46 million, and India’s was 436 million. Today, those numbers have surged to over 240 million and 1.4 billion, respectively.

Today, more than 300 million people rely on the Indus River Basin for their survival.

This has put increased pressure on the precious source of water that sits between the two nuclear rivals. The effects of global warming, and the continued fighting over the disputed region of Kashmir, has only added to those tensions.

Impact of melting glaciers

Many of the problems of today are down to what wasn’t included in the treaty, rather than what was.

At the time of signing, there was a lack of comprehensive studies on glacier mass balance. The assumption was that the Himalayan glaciers, which feed the Indus River system, were relatively stable.

This lack of detailed measurements meant that future changes due to climate variability and glacial melt were not factored into the treaty’s design, nor were factors such as groundwater depletion, water pollution from pesticides, fertilizer use and industrial waste. Similarly, the potential for large-scale hydraulic development of the region through dams, reservoirs, canals and hydroelectricity were largely ignored in the treaty.

Reflecting contemporary assumptions about the stability of glaciers, the negotiators assumed that hydrological patterns would remain persistent with the historic flows.

Instead, the glaciers feeding the Indus Basin began to melt. In fact, they are now melting at record rates.

Read full article

To Help Growers and the Grid, Build Solar on Farmland, Research Says

E360 Digest

Two new studies suggest that devoting a small fraction of U.S. farmland to solar power would be a boon both for the energy system and for farmers themselves.

In the U.S., some 46,000 square miles of farmland, an area roughly the size of Pennsylvania, is currently used for growing corn for ethanol fuel. New research investigated the impact of using a small measure of this land for solar instead.

Only a small fraction of the farms now growing corn for ethanol lie close enough to a transmission line to be suitable for a solar array. Together, these farms cover just 1,500 square miles, researchers estimate, and yet, if they were used for solar power, they would generate as much energy yearly as all the U.S. farms growing corn for fuel. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Solar installations can be a help to farms. As authors note, the land beneath solar panels can be used to grow wildflowers that draw bees, wasps, and other insects needed to pollinate crops on nearby fields. And solar arrays can provide a predictable source of income for farmers.

In some places, growers can earn substantially more from leasing their land for solar than from growing crops, though a new study of farmers in California suggests the best option may be to do both. Farmers who both produce crops and host a solar array tend to be more financially secure than those who do one or the other, according to the study, published in Nature Sustainability.

“If I’m a farmer, these two acres of solar arrays are going to pay me a certain amount of money throughout the year,” said lead author Jacob Stid, of Michigan State University. The income from solar can help offset losses from, say, a seasonal drought. Said Stid, “The conversation shouldn’t be as much about solar or agriculture, but solar and agriculture.”

Statera Energy Gets Green Light for Ambitious Green Hydrogen Project

A game-changing green hydrogen project, poised to become the UK’s largest, has secured planning approval from Aberdeenshire Council. This pioneering facility, developed by Statera Energy, promises to be a cornerstone for the UK’s low-carbon future, delivering a substantial £400 million boost to Aberdeenshire’s economy.

The Kintore hydrogen plant, designed to tap into the power of surplus wind energy, will create thousands of jobs and play a critical role in decarbonising some of the UK’s most carbon-intensive industrial areas — including Grangemouth. The project is poised to have a significant impact on the local economy. Statera predicts the creation of around 3,000 jobs during its construction phase and 300 permanent roles once operational.

At the heart of the facility’s operation is electrolysis, which produces hydrogen. The energy harnessed will come from excess wind power that would otherwise go unused, as it would be turned off to balance the grid. The project's first phase aims to deliver a storage capacity of 500 MW, with plans for future scaling to an ambitious 3 GW.

In an exciting development, Statera has outlined plans to channel the hydrogen produced at Kintore into the UK’s existing gas transmission networks, ensuring it reaches the country’s most industrialised areas. This innovative approach could help transition industrial clusters toward cleaner energy, thus playing a vital role in the nation’s decarbonisation efforts.

Aberdeenshire Council approved a comprehensive review of the project’s potential impact on the local landscape. While the scale of the facility was recognised as significant, the long-term benefits—especially in reducing carbon emissions—were deemed to outweigh any potential environmental concerns.

With the green light now given, this £400 million venture appears poised to transform Aberdeenshire into a hub for green energy innovation, while supporting the UK’s transition to a sustainable energy future.

Tom Vernon, chief executive of Statera Energy, said: “We are delighted to have secured planning approval for Kintore.

“Over the coming years, the sheer volume of wind generation coming on to the system in the UK will make electrolysers critical for harnessing wind energy that would otherwise go to waste.

“Kintore Hydrogen is designed to fully capitalise on the potential that hydrogen has to offer.

“The location and scale of this project means it can make the best use of surplus wind power, significantly lowering hydrogen production costs.

“It will help balance the grid, contribute to the UK’s energy security, and support the decarbonisation of the UK’s hard-to-abate industries and power sector.”

Read full article

https://mail.tbligroup.com/emailapp/index.php/lists/cm138dw4qa9f1/unsubscribe