Your weekly guide to Sustainable Investment

TBLI Circle

Watch TBLI Circle intro video

Join TBLI Circle, the paramount community for sustainability enthusiasts. Immerse yourself in a dynamic network that resonates with your values and commitment to sustainable practices. With exclusive events and networking opportunities, TBLI Circle empowers and brings together individuals dedicated to shaping a sustainable future. Don't miss out—join now and thrive within your sustainability tribe!

Limited-Time Deal: Explore TBLI Circle with a Complimentary 2-Week Trial!

Upcoming TBLI events

TBLI 2024 events are now online, click on the image above for a full overview and to register to individual events.

We will be adding every month more as we finalize dates and speakers. This is a great opportunity to expand your knowledge and network with like-minded individuals.

TBLI Circle Members don’t need to register

‘Litigation terrorism’: the obscure tool that corporations are using against green laws

Investor-State Dispute Settlements are legal, huge and often hush-hush – and fossil fuel firms and others are using them to hold the planet to ransom

What do you get if you cross the planet’s richest 1%, a global legal system adapted to their investment whims, and the chance to squeeze billions from governments? The answer is “Investor-State Dispute Settlements”, or ISDS, alternatively dubbed “litigation terrorism” by Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel prize-winning economist. ISDS is a corporate tribunal system, where a panel of unelected lawyers decides whether a company is owed compensation if the actions of national governments leave its assets “stranded”.

In hearings, which are often held behind closed doors, ISDS documents, claims, awards, settlements – even the content of cases – need not be made public, regardless of any public-interest considerations.

Last week the Guardian revealed how Odyssey Marine Exploration, a US-based subsea mineral extraction company, was using an ISDS panel to sue Mexico for $2.36bn (£1.87bn) after the government moved to prevent it dredging off the Pacific coast.

The company had obtained a 50-year concession over an area of sea floor off Baja California Sur, and sought a permit to mine phosphate in it. The area is a pristine breeding ground for giant grey whales and is also home to endangered sea turtles, octopus and the abalone mollusc. Odyssey said that its dredging would take place in a small area, with protection for sea creatures and measures to help “regenerate” the sea floor afterwards. But deep-sea phosphate mining entails risks of pollution, radiation and biodiversity loss, as well as damage to coastal livelihoods and communities.

When Mexico turned down the permit – once in 2016, and again, definitively, in 2018, saying Odyssey “sought to uninterruptedly dredge the sea floor” of a place “that constitutes a natural treasure and of utmost importance for Mexico and the world” – the company took it to an ISDS arbitration tribunal, arguing it was owed compensation for lost revenue.

According to the Transnational Institute, there have been 1,383 known ISDS cases to date. These courts dish out the highest average claims for damages and the highest average awards of any legal system in the world.

The panels are composed of three lawyers – one appointed by the investor, one by the state, and a president agreed by both. They are mostly white, male, business-friendly investment lawyers from the global north.

And so far it is mostly investors who have been the system’s beneficiaries, winning 61% of ISDS case decisions between 1987 and 2017, with an average award of $504m each. Fossil fuel magnates won 72% of their cases, shaking down governments for more than $77bn, according to the Transnational Institute.

The three panellists often play more than one role within the ISDS system. So-called “revolving door” and “double-hatting” practices allow lawyers to work as arbitrators, presidents or experts for both investors and states – sometimes at the same time.

This can create boundary issues when, for example, a lawyer acts as counsel for a fossil fuel investor in one ISDS case and, at the same time or thereabouts, “double hats” as the arbitrator (or president) in another ISDS case.

Allowing foreign investors to help shape these panels creates “obvious risks of bias, conflicts of interest, potential misconduct and other abuses of power”, warned the UN special rapporteur on human rights and the environment, David Boyd, in a report in October last year.

Indeed, oil companies helped to mould the ISDS system, which began in the 1960s as a way of protecting wealthy investors from the expropriation of their assets without compensation by newly independent ex-colonies.

Investors argue that ISDS protects them from arbitrary, discriminatory or unpredictable treatment in countries that might lack independent or competent judiciaries. It safeguards their “legitimate expectation” of regulatory certainty, proportionality and profit.

But investors and tribunals have also used this idea to preclude states “from taking action to address climate change, despite these actions being necessary and foreseeable for decades”, the UN report said.

The sums involved have mushroomed and can be jaw-dropping. One Singapore-based company, Zeph Investments, is suing Australia for A$300bn (£155bn) because its government turned down a proposed mining project; the company argues Australia breached free-trade treaty obligations that it relied on. In another case, Avima Iron Ore is seeking $27bn from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Faced with such claims, often “governments just capitulate,” Boyd said. The result is a regulatory chill, in which fossil fuel companies may “block national legislation aimed at phasing out the use of their assets”, as the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted.

Read full article

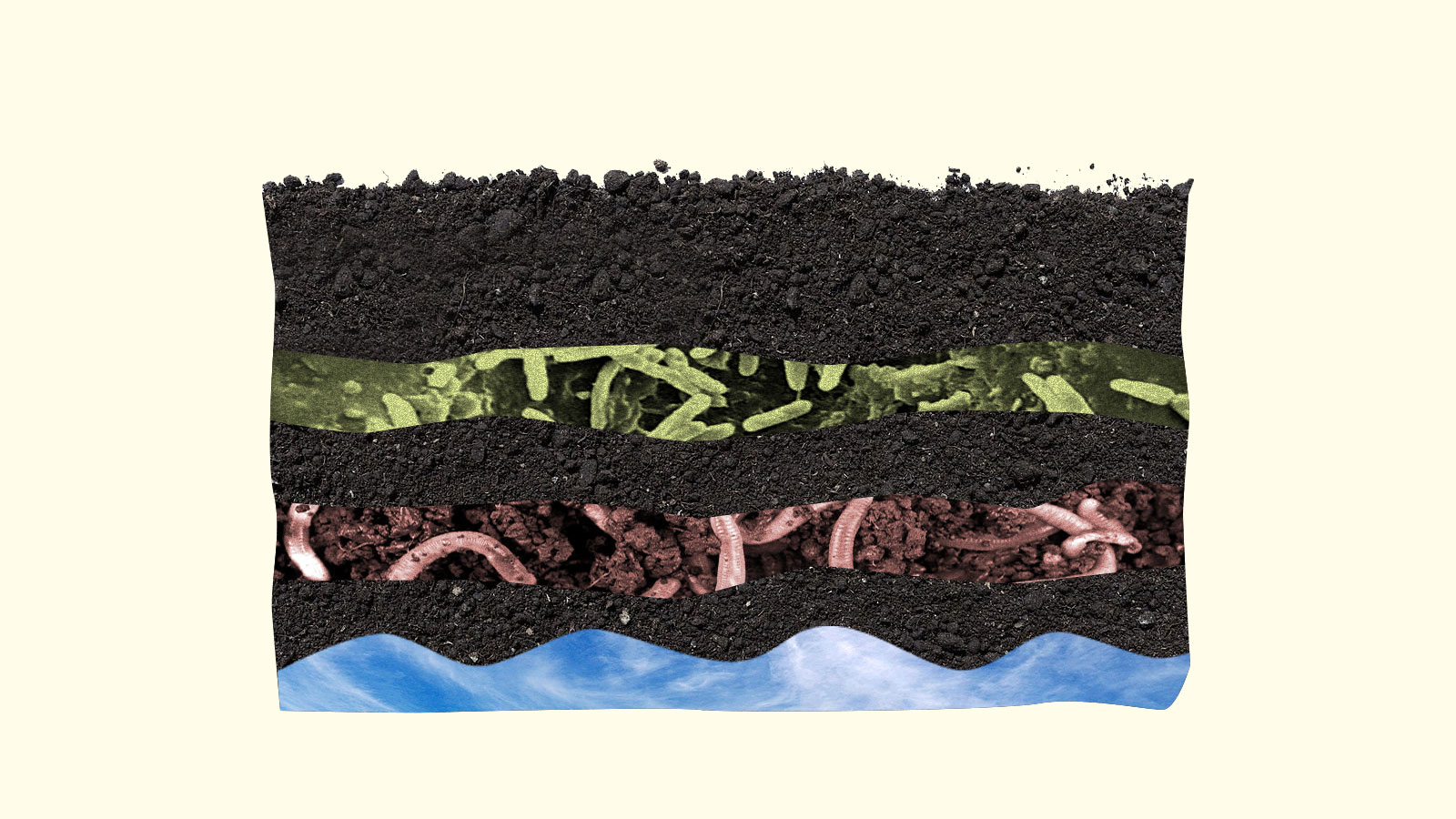

How much carbon can farmers store in their soil? Nobody’s sure.

Advocates say the long-awaited farm bill could help fix that.

Dirt, it turns out, isn’t just worm poop. It’s also a humongous receptacle of carbon, some 2.5 trillion tons of it — three times more than all the carbon in the atmosphere.

That’s why if you ask a climate wonk about the U.S. farm bill — the broad, trillion-dollar spending package Congress is supposed to pass this year (after failing to do so last year) — they’ll probably tell you something about the stuff beneath your feet. The bill to fund agricultural and food programs could put a dent in the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, some environmental advocates say, if it does one thing in particular: Help farmers store carbon in their soil.

The problem is, no one really knows how much carbon farmers can store in their soil.

“There’s still a ton of research that’s needed,” said Cristel Zoebisch, who analyzes federal agriculture policy at Carbon180, a nonprofit that promotes carbon removal.

Farmers and ranchers interact with carbon more than you might think. Draining a bog to plant rows of soybeans, for example, unleashes a lot of carbon into the air, while planting rows of shrubs and trees on a farm — a practice called alley cropping — does just the opposite, pulling the element out of the air and putting it into the earth. If America’s growers and herders made sure the carbon on their land stayed underneath their crops and their cows’ hooves, then some scientists say the planet would warm quite a bit less. After all, agriculture accounts for some 10 percent of the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions.

“We’re really good at producing a lot of corn, a lot of soybeans, a lot of agricultural commodities,” Zoebisch said, but farmers’ gains in productivity have come at the expense of soil carbon. “That’s something we can start to fix in the farm bill.”

For more than a year, climate advocates have been eyeing the bill as an opportunity to increase funding and training for farmers who want to adopt “climate smart” practices. According to the Department of Agriculture, that label can apply to a range of methods, such as planting cover crops like rye or clover after a harvest or limiting how much a field gets tilled. Corn farmers can be carbon farmers, too.

But experts say the reality is a bit more opaque. There’s still a lot that scientists don’t know about how dirt works, and they disagree about the amount of carbon that farmers can realistically remove from the air and lock up in their fields.

Zoebisch and other advocates say that for the farm bill to be a true success, it’ll have to go even further than incentivizing carbon farming. Congress, they say, should also fund researchers to verify that those practices are, in fact, removing carbon from the atmosphere.

Read full article

Trinidad & Tobago says oil spill from mystery vessel is national emergency

Upturned and largely submerged vessel of unknown origin is leaking hydrocarbon off south-west coast or Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago’s prime minister has said that a large oil spill near the twin-island nation has caused a “national emergency” and vowed that the government will spare no expense to help rehabilitate the island’s beaches.

Oil from the spill has coated numerous beaches on Tobago’s south-west coast, and the government has yet to identify the owner of the vessel that was found overturned off the coast last week.

The prime minister, Keith Rowley, said it was not immediately clear how much oil had spilled and how much remained in the largely submerged vessel. Nor was it clear what caused the vessel to overturn.

“An unknown vessel has apparently drifted upside down into Tobago. That vessel, we don’t know who it belongs to. We have no idea where it came from and we also don’t know all that it contains,” he said at a press conference reported by the Trinidad & Tobago Newsday.

“What we do know is that it appears to be broken and is leaking some kind of hydrocarbon that is fouling the water and the coastline,” Rowley added. “That vessel could have come to us from any kind of operation, especially if the operation is illicit.”

Farley Augustine, chief secretary of Tobago’s house of assembly, said divers had not been able to contain the leak and were trying to determine how to remove the remaining oil.

Rowley said that the costs of the cleanup were likely to be high. “This is a national emergency and therefore it will have to be funded as an extraordinary expense … You have to find the money and prioritise. So this is priority and we have to respond,” he said, adding that “some not-so-insignificant costs are being incurred just to respond to this incident”.

But he warned that “cleaning and restoration can only seriously begin after we have brought the situation under control. Right now, the situation is not under control. But it appears to be under sufficient control that we think we can manage.”

Source

Rising capital costs thwarts clean energy in emerging economies

Many emerging market and developing economies are missing out on clean energy investment as the high cost of capital for new projects is deterring developers, particularly for some of the world’s poorest countries, a new International Energy Agency (IEA) report finds.

Global clean energy investment has risen by 40% since 2020, reaching an estimated $1.8 trillion in 2023, but almost all the recent growth has been in advanced economies and in China. By contrast, other emerging and developing economies account for less than 15% of total investment, despite being home to 65% of the world’s population and generating about a third of global gross domestic product, IEA said. Capital flows to clean energy projects in many emerging and developing economies remain low.

To get on track for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C, IEA says clean energy investment in emerging and developing economies outside China needs to increase more than sixfold, from $270 billion today to $1.6 trillion by the early 2030s. The availability of concessional finance – primarily from international development finance institutions – would also need to triple within this timeframe, IEA said. Additionally, almost half of the total clean energy investment over the next ten years in emerging and developing economies outside China would need to go to utility-scale solar and wind projects, electricity networks, and spending on more energy-efficient building designs and appliances, the report said.

Some clean energy technologies, such as solar PV and onshore wind, are already cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives in many parts of the world. But the report highlights that the cost of capital, or the minimum expected financial return to justify an investment, for utility-scale solar PV projects in emerging and developing economies was more than twice that in advanced economies. The report says that narrowing the gap in the cost of capital between emerging and developing economies, on the one hand, and advanced economies, on the other, by 1% could reduce these financing costs for clean energy by $150 billion annually.

“There are huge, cost-effective opportunities for emerging and developing economies to meet their rising energy needs with clean technologies, but financing has to be affordable as well,” said IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol. “Reducing risk through clear and timely regulation is a first step to attract investment. This needs to be underpinned by a significant increase in financial and technical support from the international community. We have to build new bridges between investors looking for clean energy opportunities and the markets where this investment is most needed.”

However, the IEA says almost all the required investments are in mature technologies and in sectors where there are tried and tested policy formulas. About 5% of the total clean energy investment needs through 2035 are in sectors that depend on nascent technologies like low-emissions hydrogen, hydrogen-based fuels, or carbon capture, utilization, and storage, the report said.

Source

Atlantic Ocean circulation nearing ‘devastating’ tipping point, study finds

Collapse in system of currents that helps regulate global climate would be at such speed that adaptation would be impossible

The circulation of the Atlantic Ocean is heading towards a tipping point that is “bad news for the climate system and humanity”, a study has found.

The scientists behind the research said they were shocked at the forecast speed of collapse once the point is reached, although they said it was not yet possible to predict how soon that would happen.

Using computer models and past data, the researchers developed an early warning indicator for the breakdown of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (Amoc), a vast system of ocean currents that is a key component in global climate regulation.

They found Amoc is already on track towards an abrupt shift, which has not happened for more than 10,000 years and would have dire implications for large parts of the world.

Amoc, which encompasses part of the Gulf Stream and other powerful currents, is a marine conveyer belt that carries heat, carbon and nutrients from the tropics towards the Arctic Circle, where it cools and sinks into the deep ocean. This churning helps to distribute energy around the Earth and modulates the impact of human-caused global heating.

But the system is being eroded by the faster-than-expected melt-off of Greenland’s glaciers and Arctic ice sheets, which pours freshwater into the sea and obstructs the sinking of saltier, warmer water from the south.

Amoc has declined 15% since 1950 and is in its weakest state in more than a millennium, according to previous research that prompted speculation about an approaching collapse.

Until now there has been no consensus about how severe this will be. One study last year, based on changes in sea surface temperatures, suggested the tipping point could happen between 2025 and 2095. However, the UK Met Office said large, rapid changes in Amoc were “very unlikely” in the 21st century.

The new paper, published in Science Advances, has broken new ground by looking for warning signs in the salinity levels at the southern extent of the Atlantic Ocean between Cape Town and Buenos Aires. Simulating changes over a period of 2,000 years on computer models of the global climate, it found a slow decline can lead to a sudden collapse over less than 100 years, with calamitous consequences.

The paper said the results provided a “clear answer” about whether such an abrupt shift was possible: “This is bad news for the climate system and humanity as up till now one could think that Amoc tipping was only a theoretical concept and tipping would disappear as soon as the full climate system, with all its additional feedbacks, was considered.”

It also mapped some of the consequences of Amoc collapse. Sea levels in the Atlantic would rise by a metre in some regions, inundating many coastal cities. The wet and dry seasons in the Amazon would flip, potentially pushing the already weakened rainforest past its own tipping point. Temperatures around the world would fluctuate far more erratically. The southern hemisphere would become warmer. Europe would cool dramatically and have less rainfall. While this might sound appealing compared with the current heating trend, the changes would hit 10 times faster than now, making adaptation almost impossible.

“What surprised us was the rate at which tipping occurs,” said the paper’s lead author, René van Westen, of Utrecht University. “It will be devastating.”

He said there was not yet enough data to say whether this would occur in the next year or in the coming century, but when it happens, the changes are irreversible on human timescales.

In the meantime, the direction of travel is undoubtedly in an alarming direction.

“We are moving towards it. That is kind of scary,” van Westen said. “We need to take climate change much more seriously.”

Source